Inclusive education and spinal cord injury

Listening to the school experiences of children and young people who have spinal cord injuries is critical to understanding how to make inclusion happen. By considering the perspectives of children and young people who have already gone through the process of inclusion, we can better grasp what difficulties they face, what strategies helped to welcome and include them and the importance of involving them in the process.

Introduction

“I am delighted to introduce this toolkit on behalf of Back Up. Having had a spinal cord injury from birth, I have experienced the relationship between spinal cord injury and education from nursery to university. As such, I fully understand the importance of this resource. As a proud trustee of Back Up, I am a firm advocate of the support that they provide to ensure students with spinal cord injury are fully included in every aspect of their school lives.

“Including a spinal cord injured child or young person in mainstream school must be taken seriously.”

With these formative years being of such significance, inclusion must be seen as a non-negotiable priority. Whether injured from birth like myself, or injured during school years, it is likely that many of the general questions and concerns will be similar. For example, a child may be worried about differential treatment from both teachers and friends, whether they will have equal access to facilities and classrooms within the school and whether they will be able to attend the much loved and anticipated school trips. In addressing these common concerns, it is of utmost importance to appreciate the need for tailored solutions for each child. Only then will a child be included appropriately and given the opportunity to reach their full potential in a meaningful way.

I was born with a childhood tumor known as neuroblastoma. Having known no different, and with an older brother and sister to look up to, I was adamant that my time at school should be as close to ‘normal’ as possible. To me this meant competing at sports day, participating in PE lessons in the school pool and attending school trips. Unfortunately, throughout my schooling, barriers to this level of inclusion were often encountered. However, just as quickly as barriers arose, through pragmatism and determination they were often overcome. My experience demonstrates that inclusion is a genuine possibility that should be striven for and not shied away from. Support from Back Up and this toolkit represent invaluable resources to be drawn upon to ensure that inclusion occurs. I know that my school would have benefited hugely from additional assistance and outside, expert help in this regard. I am fortunate that my schooling experience is not tainted by a lack of inclusion, however the same cannot be said for everyone. Ultimately, this toolkit can make the process of inclusion so much easier and help to eliminate the number of children who are unable to look back at their schooling through the same positive lens as myself.

Practical advice is important, as is the need to consider each child’s situation individually. This step can often be overlooked and lost in the process of formal procedures. Communicating and taking time to recognise a child or young person’s perspective should be given the respect it deserves. By reading testimonies directly from students in this toolkit, you will gain insight into their experiences and understand just how important it is to ensure inclusion is practised every day.”

Ben Sneesby, Trustee

The need for inclusive education

This section outlines why Back Up have produced this toolkit, by highlighting the research which evidences the need for inclusive education.

‘‘Back Up’s education inclusion service provides education and support to staff at nurseries right through to university in understanding what is needed, and perhaps more importantly what is not needed, by children and young people with a spinal cord injury. In my experience, schools often are unaware and can struggle to make activities inclusive to all.’’

Cheryl Ali, Occupational Therapist, Spinal Cord Injury Centre at the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital, Stanmore.

Back Up’s vision is a world where people affected by spinal cord injury can realise their full potential. As the only charity in the UK that runs dedicated services for children and young people with a spinal cord injury, we believe that they have the right to a fulfilling and active life. We inspire people affected by spinal cord injury to get the most out of life.

‘‘The key question is ‘How are we going to do it?’ – Not ‘can we do it?’’’

Head Teacher, primary school

We knew from listening to children and young people and their families that there was a need to support educational institutions in creating an inclusive environment for all children and young people with a spinal cord injury. We recognised that – with our wealth of experience in this area – we were well placed to meet this need.

Spinal cord injury in children and young people is relatively rare, but the complexity of managing medical, social and emotional needs can be daunting. When done well, the impact on the young people is lifelong, and the rewards for the individual, their family, the education institution and the state are immeasurable. Many contributors to this toolkit have thrived through the good practice illustrated here and have gone on to be solicitors, communications experts and Paralympic athletes.

Our values run through this toolkit and are illustrated in the stories and quotes that bring our advice and experience to life:

- Driven by the needs of people with spinal cord injury, we are passionate about transforming lives

- Through challenge and fun we open up possibilities to develop, achieve and get the most out of life

- We respect individuality and embrace diversity

- We strive for quality and excellence in all we do

The need

Spinal cord injury is permanent. It could be the result of an illness or something as simple as falling down the stairs. Spinal cord injury can affect anyone at any time.

At Back Up, we understand that spinal cord injury can be devastating. But we’re here to inspire everyone to get the most out of life. Children and young people with a spinal cord injury are more likely to be unemployed and experience lower community participation when they reach adulthood. They are also less likely to live independently or get married.

People affected by spinal cord injury are at the heart of everything Back Up does and every decision we make. Our work is led by need. Understanding published research into needs, together with our own research into the needs of specific groups of people, has helped to inform the way we deliver our services and what our strategy is for the future development of Back Up.

The education inclusion service was set up in 2009 in response to research conducted by the Institute of Education into the school lives of children and young people with a spinal cord injury. That need is as relevant now as ever, but with our support we know that full inclusion of children and young people with spinal cord injury at their nursery, school, college or University can and should be achieved.

Models of disability

Models of disability provide a framework for understanding the way in which people with impairments experience disability. They also provide a reference for society as laws, regulations and structures are developed that impact on the lives of disabled people. This section looks at some models of disability, what inclusive education means and how circles of support can facilitate inclusion.

Models of disability

Models of disability provide a framework for understanding the way in which people with impairments experience disability. They also provide a reference for society as laws, regulations and structures are developed that impact on the lives of disabled people.

Two main models which are frequently discussed are the ‘medical model of disability’ and the ‘social model of disability’. The medical model views disability as a feature of the person, directly caused by disease, trauma or a health condition. It calls for medical treatment or intervention, to ‘correct’ the problem with the individual. The social model sees disability as a socially created problem, not an attribute of the individual. It is society which ‘disables’ people through being designed in an inaccessible way and through disabling attitudes.

There is also the bio-psychosocial model of disability, which sees disability as an interaction between a person’s health condition and the environment they live in. It advocates that both the medical and social models are appropriate, but neither is sufficient on its own to explain the complex nature of one’s health. The bio-psychosocial model is useful to understand the support that spinal cord injured young people, their families and schools may need to ensure full inclusion in mainstream education.

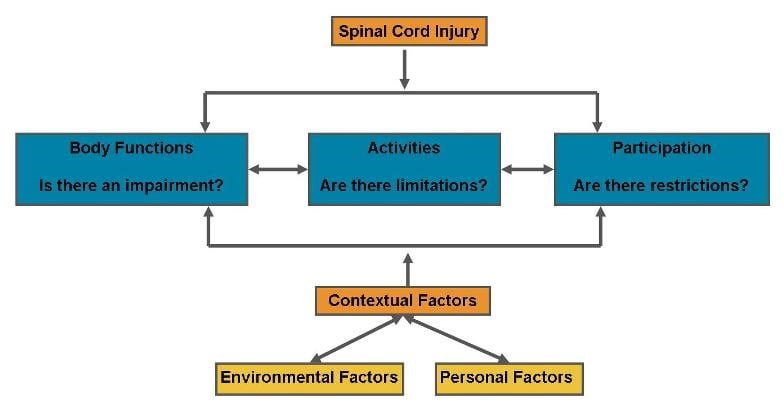

Model of bio-psychosocial model:

(Amended from the World Health Organization’s The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health)

This bio-psychosocial model shows the complex and dynamic relationship between a number of inter-related factors. In this model a person’s ability to function is viewed as the outcome of the interactions between the medical factor (spinal cord injury) and contextual factors.

The contextual factors include external environmental factors such as social attitude and buildings, and internal personal factors, which include coping styles, social background, education and other factors that influence how disability is experienced by the individual.

The diagram identifies the three levels of human functioning:

- Body Function

- Activities

- Participation

Within this model disability occurs when one or more of these levels of function are not working to their full potential: are there impairments in body function such as a significant loss of movement; are there limitations a person may have in doing activities; are there restrictions that a person may experience in participating or being

included in life situations.

Back Up feels that understanding how these levels and the contextual and medical factors are connected, and how they impact on each other, is crucial to effectively supporting people with a spinal cord injury to realise their full potential.

Model of adjustment post spinal cord injury

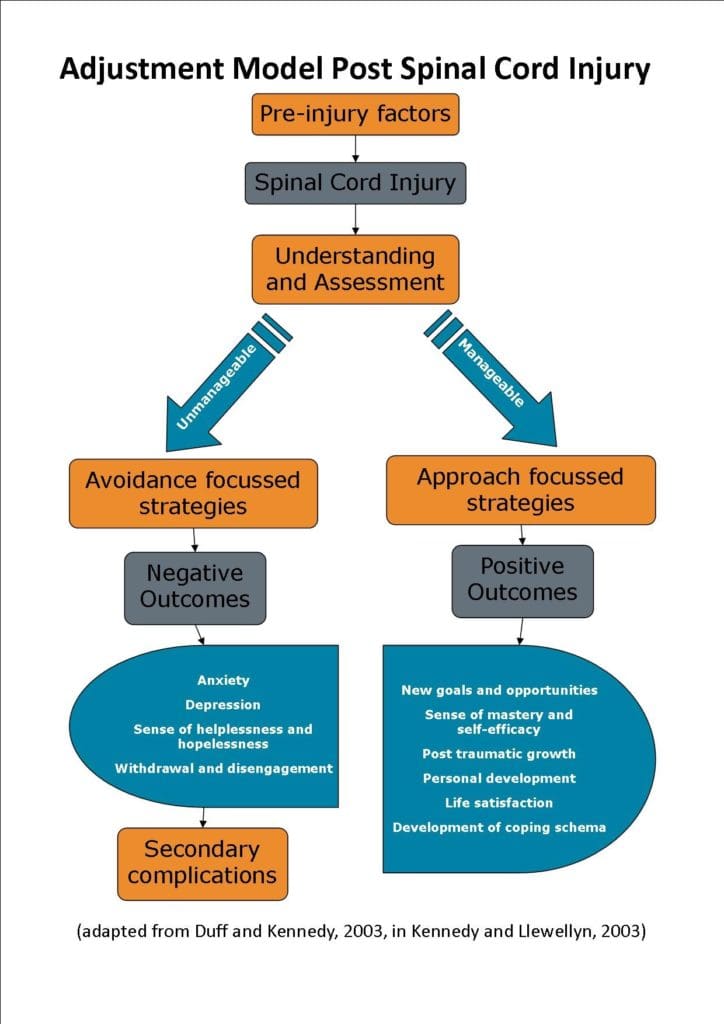

Personal and social factors will affect how a person initially perceives their situation as a person with a new spinal cord injury. Different people, at different times, may perceive their situation as unmanageable, or as a manageable challenge.

The scientific evidence shows that those that are able to perceive their situation as a manageable challenge will employ certain kinds of approach focused coping strategies such as using support available, and taking on challenges, building up their confidence and skills and adjusting emotionally to their situation, with long-term positive outcomes in life.

Those that see their situation as unmanageable will tend to use coping strategies aimed at avoiding the situation, such as disengagement from rehabilitation, withdrawal, alcohol and drug use. These behaviours on a long-term basis often lead to depression, anxiety and self-neglect resulting in hospitalisation for pressure sores and urinary tract infections.

Approach focused strategies include:

- Using emotional and practical support (friends, family, school)

- Behavioural activation – being included at school, having meaningful activities, accessing leisure services

- Acceptance – being able to talk about the situation, accept the reality of the situation

- Active problem solving and goal setting

- Positive reinterpretation – believing that something good can come out of the situation

This adjustment model helps to show how the schools and families inclusion service links to long-term positive life outcomes for children and young people with a spinal cord injury. Supporting schools to provide emotional and practical support, ensuring that the child or young person is fully included in all aspects of school life, and that the school environment encourages them to talk about their situation openly, will lead to more positive long term outcomes for children and young people with a spinal cord injury.

“Inclusive education means, to me as a parent of a child with a spinal cord injury, awareness. It’s staff knowing the child’s needs. It’s not just about having ramps and things like that. It’s a triangle between the parents, school and the student. And if you haven’t got that communication, no matter what facilities are in place you won’t have the inclusion.”

Janet, mum of son age 16

Inclusive education is a social justice issue because it creates a society that values all equally – not only does it benefit disabled students, but all students, because they learn the strength of diversity and equality, lose their fear of

difference, and develop empathy for others. It is as much about recognising our similarities as it is valuing and respecting our differences. Feeling part of our families and our communities from the beginning of our lives increases our sense of citizenship. Tara Flood CEO, Alliance for Inclusive Education

Inclusive education enables all students to fully participate in any mainstream early years provision, school, college or university. Inclusive education provision has training and resources aimed at fostering every student’s equality and participation in all aspects of the life of the learning community.

Inclusive education aims to equip all people with the skills needed to build inclusive communities.

Inclusive education is based on seven principles (taken from the Alliance for Inclusive Education website):

- Diversity enriches and strengthens all communities

- All learners’ different learning styles and achievements are equally valued, respected and celebrated by society

- All learners to be enabled to fulfill their potential by taking into account individual requirements and needs

- Support to be guaranteed and fully resourced across the whole learning experience

- All learners need friendship and support from people of their own age

- All children and young people to be educated together as equals in their local communities

- Inclusive Education is incompatible with segregated provision both within and outside mainstream education

“When I went back to school back into physical education there was a few times that the sport they chose to play wasn’t suitable for a wheelchair user and I decided that I didn’t want to sit and just watch them playing sports for an hour. So I went up to my teacher and I said to him that obviously I can’t play football but can I referee the match? I quite enjoyed it, even though I wasn’t taking part in the full game.”

Dean, 15

The seven principles of inclusive education clearly link with the approach focused strategies outlined in the adjustment model, which are proven to lead to positive outcomes for people with a spinal cord injury.

“We have been made aware of how many different people need to be on the team to provide the support. If everyone can tackle something within their area of expertise, and we are all given a broadened awareness, then the support given is much better.”

SENCO, Gloucester

Resources

- Scope website: more detail about the medical and social models of disability

- Alliance for Inclusive Education: website on inclusive education

What do children and young people say

Listening to the school experiences of children and young people who have spinal cord injuries is critical to understanding how to make inclusion happen. By considering the perspectives of children and young people who have already gone through the process of inclusion, we can better grasp what difficulties they face, what strategies helped to welcome and include them and the importance of involving them in the process.

Most research on children and young people with spinal cord injuries focuses on medical aspects of their lives. Little has been done around their social and school experiences. Recognising the vital importance of these perspectives, Back Up commissioned the Institute of Education to conduct research into these areas in 2008: The school lives of children and young people with a spinal cord injury.

The report found that ‘the ethos and attitude of the school towards disability largely determines the quality of the school experience for spinally injured children and young people, including their levels of inclusion in whole school activities and independence.’ Creating an inclusive ethos and school culture is the most important step schools can take when welcoming a student with a spinal cord injury back to their school community.

Other findings from the report are found throughout this toolkit in relevant sections. Highlights are summarised below according to different categories:

Returning to school

- Most students in the study obtained their injury in childhood or adolescence, meaning they had to return to the school they had previously attended. For many, returning to school was ‘a difficult and sometimes traumatic event.’

- The process of returning can be improved through hospital visits and communication, early meetings with the young person and family to discuss requirements, and support to re-establish friendships.

- Adaptations and adjustments necessary for appropriate access to school should be made as quickly as possible to ensure a sufficient welcome for the student. This often requires schools being proactive and supportive local authorities.

- Many students who return to school report still not being able to access some parts of the school.

- Adaptations that had been made to schools were rarely straightforward. Children and young people often found that ramps were too steep, specialist equipment restricted their independence, and ‘disabled’ toilets were inadequate or unavailable.

“I was extremely scared about going back to school. I just didn’t like the idea of going back. My school were really good. They were eager to get me back. The teachers were understanding about everything like if I wasn’t well or couldn’t go in or if I had a hospital or doctor’s appointment. They understood that it was not going to be the same as before. They gave me extra time to do things.”

Danielle, 17

Social life and friendships

- Health-related activities like physiotherapy sometimes interfered with social time and lessons.

- Maintaining and making friendships was seen as more difficult for the children and young people with spinal

cord injury. The ethos of the school, well written policies and procedures and efforts of staff to include (rather than separate) students had a positive effect on friendships.

Physical education and physical activity

- Many activities for children with a spinal cord injury tend to be sedentary and set at home. There is a need for more unstructured play and outdoor activities, in addition to structured recreation.

- Some young people with a spinal cord injury felt excluded or sidelined from PE and sports. Others felt more included, and the ‘difference appeared to be determined by the attitudes and knowledge of the PE staff’.

- School swimming activities posed particular challenges, including appropriate changing facilities, transport, hoist and water temperature.

Transport and school trips

- Transport to and from school was reported to be a problem for many young people. Problems included very early pick up, taxis not turning up, and lack of flexibility.

- Issues with transport often impacted negatively on students’ ability to attend trips outside school.

Role of Teaching Assistants

- The role and relationship of teaching assistants (TA’s) is a critical one in the inclusion of children and young people with spinal cord injury. Qualities that children and young people liked to have in teaching assistants included a caring nature, clear boundaries and sensitivity to their need for socialisation without being overly protective.

- TA’s need training that reflects the multi-faceted nature of their jobs. In addition to appropriate training on practical issues like manual handling and using a hoist, they also need information on how to support young people’s social, emotional and psychological well being.

“My advice is to talk to the student, don’t feel bad or embarrassed or shy about talking to them about their spinal cord injury. This might seem like a little thing but it can make a huge difference to the student. Asking them what they want is so important.” Ben, 17

Read more about what Hannah, 18 says about her experiences of having a teaching assistant.

Co-operation and information sharing

- The cooperation between professionals involved in a young person’s care and return to school is essential but

also difficult to manage. Tensions were reported to exist between health and education, particularly in regard to funding specialist equipment and how to prioritise health and education needs. - Partnerships between schools and parents were important and succeeded when both were ‘open and receptive to learning, sharing information and expertise.’

“I was more scared about how people would react to me and how I would be able to make friends. I found it really difficult at first to make friends.” Laura, 18

Independence, participation and ambitions of young people at school

- For many young people, there was little consultation about disability issues at school beyond their annual review. These should be developed in schools aiming to include children with specific requirements so that they have a say in how independent they are and how they want others to help them.

- Independence levels of children and young people with spinal cord injury varied significantly depending on many factors, such as accessibility of the school, confidence of the staff and TA’s to allow for independence, and the willingness of the school to be flexible about health and safety rules.

- The independence and participation of disabled young people should be emphasised in a school’s inclusion agenda.

- Most young people interviewed were ‘highly ambitious and their future plans included training for the Paralympics, studying at University or FE colleges’, but also wanted more comprehensive, better quality careers advice.

What needs to change in schools to make sure everyone is included?

A focus group was run by Back Up involving young people with a spinal cord injury, a group of young volunteers and Back Up volunteers. The focus group looked at the question above and responded with the following:

Attitudes

- Asking individuals what they want!!

- Recognition that it is our needs and requirements (not our wants) which need addressing, and providing for them, so that people are not made ‘special’, or at risk of being bullied.

- Sensitivity to pupils who, for reasons of their own, do not want to be included in all areas possibly because of their needs and reactions to noise, light, crowds etc.

- Learning and teaching on non-judgemental attitudes.

- Learning and teaching about minority issues and groups in a worldwide context.

- Team building for kids as well as teachers!

- Many role model staff and visitors to schools of people with a wide range of needs and lifestyles.

- No separation of disabled and non-disabled pupils from the start, so that all are seen as individuals.

- Sport used to mix people socially and ability wise so they learn from each other and enjoy themselves together.

“When I went to high school I was wrapped up in cotton wool, not by my parents but by the teachers, by the school in general and the system. The attitude was that I was in a wheelchair and that I couldn’t do anything and that I’d need loads of help. I wanted to be just like everyone else and that prevented it.”

Laura, 18

Disability awareness

- Training for teachers, support staff and all people who work in schools on disability awareness and equality.

- Specialist staff who can identify issues and difficulties, and make sure pupils are supported.

- Fun and participatory teaching and learning techniques.

- Learning about disability issues which is taught by disabled people themselves.

- Very sensitively handled provision of learning support – not in your face!

- Willingness to join the fight for our rights and the rights of our peers in the light of the Equality Act.

Access and equipment

- Braille, lifts, accessible loos, interpreters, note takers etc.

- Good quality equipment which is helpful, but not intrusive of our making of friendships.

- Access to grants (via internet sources and teacher ‘know how’) so that we can look after a lot of our own needs.

- Well designed spaces and buildings to enhance everyone’s participation.

- Space in schools for ANY kids to retreat a little when they need to.

- Good access (including transport) to high quality out of school experiences, and especially school trip and journeys nobody left out!

- Links between schools and groups of staff (teachers, supporters etc.) locally and nationally.

- School councils with equality of representation.

- Medical and therapy appointments during out of school hours, so as not to interfere with schooling and keep people the same

All information from Knight, A, Petrie, P, Potts, P and Zuurmond, M. (2008) The school lives of children and young people with a spinal cord injury. Thomas Coram Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London. Report to Back Up.

Understanding Spinal Cord Injury

It is important to understand the medical requirements of those who have spinal cord injuries, but it is equally crucial to recognise that each person will be affected individually and have unique physical, social, emotional and academic requirements dependent on their situation.

There are an estimated 50,000 people in the UK living with a spinal cord injury and each year approximately 2,500 people are newly injured.

At Back Up we understand that a spinal cord injury can be devastating, but we believe that it should not prevent anyone from getting the most out of life. With the right support most people will cope and adjust well to the new requirements of their lives in the long term. For children and young people, re-connecting to their education and social lives is a critical piece of this support.

Spinal cord injury is sudden and the impact on an individual can be huge. It is not just about a loss of mobility but also the effect on bodily functions. Aside from the physical impact, spinal cord injury can have a significant psychological impact on the person with the injury and their family.

Depression and anxiety are not uncommon in those affected by spinal cord injury. Many people feel that the things most important to them in life may never be the same (whether family, relationships, hobbies and recreation, work, social life, travel, or any area of life). It is common to feel uncertain about the future.

For more information about how damage or injury to the spinal cord impacts someone, take a look at our page ‘What is spinal cord injury?‘.

Children and young people with a spinal cord injury

While spinal cord injuries for children and young people are rare, the causes are also very varied. The most common causes leading to a spinal cord injury are falls and road traffic accidents. Some spinal cord injuries can be the result of a virus, such as Transverse Myelitis, or a tumour on the spine. Other, rarer, aetiologies

include those arising from violence, such as gun shots or stab wounds, and birth injuries.

Spinal cord injuries are usually classified into two main groups: tetraplegic and paraplegic. Quadriplegic is the American term for tetraplegic.

A tetraplegic injury means damage has occurred to the spinal cord at the level of the cervical vertebrae. This will involve the loss of movements and sensation in all four limbs. A paraplegic injury occurs from the thoracic vertebrae down and involves loss of movement and sensation in the lower half of the body. Please see the diagram for more

detailed information on functions for different levels of injury.

The symptoms of a spinal cord injury depend on the severity of the injury but include: muscle weakness and spasms, breathing problems, loss of feeling in the chest, arms and legs, and loss of bowel and bladder function.

The extent of the paralysis also depends on whether injury to the spinal cord is complete, or incomplete. If an injury is incomplete, only part of the spinal cord is damaged and some messages still get through. This means that some or all sensation and movement can exist from below the point of injury. If someone has a complete lesion, however, total paralysis will result below the point of injury and there will be no movement or sensation from this level.

Having a spinal cord injury is likely to mean having mobility difficulties though these vary considerably. Some people are able to walk a little; some need help to walk with crutches or a walking frame, while others need to use a wheelchair permanently. A spinal cord injury affects bladder and bowel control, so children and young people with

a spinal cord injury may use urology aids such as a catheter or sheath and may need help managing this.

There is more information on the health issues after a spinal cord injury in section 2a, Knowing what to expect.

“At Stoke Mandeville, we have a strong research and clinical background, and from that are able to say that most people adjust and cope really well in the long term and do go on to do really well and get back to school and education and create relationships. This is a really important message to get across.

”It’s not the norm that people with a spinal cord injury have long-term psychological trauma and difficulty. It’s more normal to cope and make adjustments.”

Zoe Chevalier, Clinical Psychologist, Stoke Mandeville Spinal Injury Unit

References

- Knight, A, Petrie, P, Potts, P and Zuurmond, M. (2008) The school lives of children and young people with a spinal cord injury. Thomas Coram Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, Report to Back Up